this is not a review...this is my bias, part 1: losing friends

In three reviews from 2025's Melbourne International Comedy Festival I want to see where my bias might lead me as a critic, and think about where it has led me already. I want to try and lose friends.

MARK FISHER: ‘Is it an occupational hazard as a critic to lose friends?’

MICHAEL BILLINGTON: ‘That’s the price you pay.’

Critical Stages/Scenes critiques (2019).

‘It feels like punching a pal’ is the perfect title for an essay asking what theatre criticism in close-knit communities like Naarm can feel like. It’s the name of a Substack newsletter by Exeunt Magazine, a UK-based outlet that asked four theatre reviewers about their experience being a critic in a small city. Locations (Sheffield, Edinburgh, Liverpool) vary as much as answers but the take away is unsurprising: it’s hard. ‘There are several challenges to working within Scotland’s close-knit theatre community,’ writes Edinburgh-based critic Fergus Morgan, ‘but finding the courage to be critical about people I know and like is the biggest.’

It was Andrea Long Chu, the Pulitzer-prize winning critic and viral master of the hatchet job (what Merve Emre once called ‘rigorous negativity’) likened writing criticism to a ‘very aggressive form of friendship.’ I think she was looking for a metaphor to represent the intimate and dynamic character of the style of critical discourse she pursues. When we understand engaging with art in criticism as a form of ‘friendship’ it becomes a complex process of relating - tense, mutable, reciprocal. But Chu is not a theatre critic (though definitely a theatre kid: check out her hit piece on Andrew Lloyd Webber). It’s hard for friendship to exist purely as a metaphor for criticism’s form in a field where reviewing one’s friends is a material condition of the work. Frank Peschier, a critic from Liverpool, puts it this way in his contribution to Exeunt’s newsletter: ‘…love the show and you risk being accused of nepotism, hate it and you risk glares and ostracization from yoga.’

Found dead: one Cameron Woodhead in a long black jacket, bludgeoned by bombastic side eye at Collingwood Pilates.

It’s easy to have an aggressive friendship with an artist you’re not actually friends with, in other words. Or to think criticism can be friendly (or friend-making) when that artist you’re panning is well-established, and even likely to receive an economic boost from the exposure that your 10,000-word viral review gives them. The stakes are low enough for the venom to be sucked out of discourse, by which I mean its potential to cause personal ‘harm’ to the reviewed is mitigated. Plus the word count is large enough for any artist to at least feel seen and known before they’re devoured.

Form matters here too. Chu doesn’t do star ratings, or short 150-word reviews. For Melbourne International Comedy Festival this year, Time Out Melbourne replaced their usual 400 - 600-word reviews with quick 100-worders. Can one make a friend in so little words? Or write discourse that can withstand the metaphorical comparison to friendship, with all its tensions and charms; ebbs and flows? And what about the material pressures of a freelance labour market, especially one concentrated into smaller communities? The question is not only whether we can write ‘aggressive friendship’ but, as Namwali Serpell writes in The Yale Review, ‘whether we can find work that doesn’t alienate us from itself, and from each other’. Is that the ‘occupational hazard’ that Mark Fisher flags in my epigraph?

In a three-part newsletter, I’m going to explore these questions by reviewing three friends who had shows at this year’s Melbourne International Comedy Festival: Lou Wall (Breaking the Fifth Wall), Mel O’Brien & Samantha Andrew (No Hat, No Play!) and Jarryd Prain (Hanky Code). Call it the Father, Son and Holy Ghost of my personal bias. I want to see where my bias might lead me as a critic, and consider where it has led me already. I want to try and lose my friends. Or I want to try and write theatre criticism as an aggressive form of my friendship with them.

When we’re talking about bias we’re talking about personal context. And it’s the function of the personal that connects every one of these three shows I’m reviewing. They ask what form the personal should take in comedy in 2025. And so do I. What form should my personal context take as I analyse that form? Call it criticism as a hall of mirrors reflecting myself reflecting on them reflecting on themselves. By following that mis-en-abyme as it refracts, I’ll ask what form a personal relationship can, or should take in a community as close-knit and tightly wound as Naarm’s independent theatre scene.

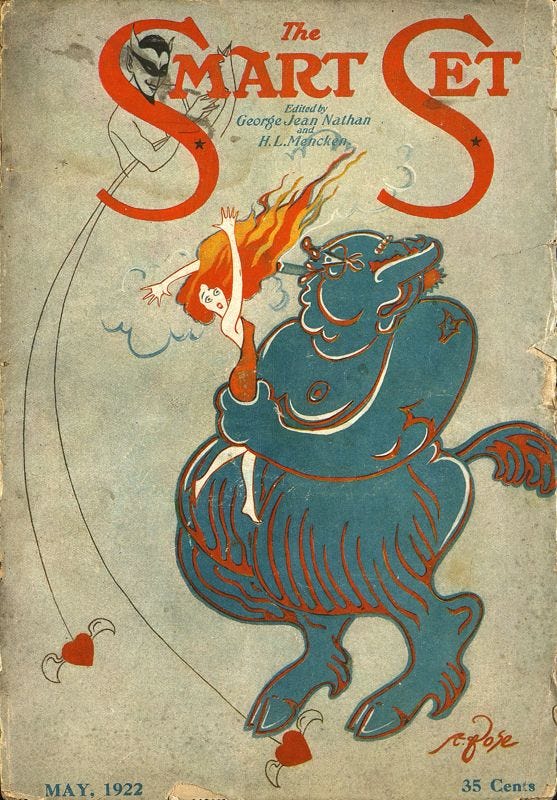

I want to start by teasing out this idea of ‘personal criticism’ with an anecdote from 1922 - when the American critic George Jean Nathan wrote that ‘there is no such thing as an impersonal critic because there is no such thing as an impersonal person’. At that point he had been co-editing the New York-based magazine Smart Set for ten years. He took his own advice soon after while reviewing Bernard Shaw’s five-part Back to Methuselah. He begins by listing the ailments he felt during the show’s ‘eleven hour runtime’: ‘three cramps…a touch of lumbago..an attack of trigeminal neuralgia…nervous debility…a sore knee from pressing for four hours the seat in front of me’. If theatre criticism is ‘a matter of individual expression’ like any art, as Nathan insists, then the individual here has a stiff neck and fucking loves complaining.

It’s Brené Brown-style theatre reviewing - a faux vulnerability intended to connect you to the reviewer, as if reading is a personal relationship rather than a one-sided monologue you can disagree with from a dead guy you don’t know. Critical anonymity is dismantled one mid-show cramp at a time. From this exaggerated position of intimacy Nathan seems more authentic. In seeming more authentic he can be authoritative without seeming too diminutive. He can judge Shaw - quite brutally: ‘It does not touch the heart; it does not thrill’ - without appearing like he’s punching down. How can you, dear reader, dispute someone’s cramps, even if you disagree with their cause. Gotcha.

Obviously Nathan is giving us a fine-tuned performance of subjective experience rather than a truly authentic recount of that experience. We are reading someone fashion their reviewing persona to a fine, authoritative point that cultivates a tone of authenticity intended to position us, his readers, as his friends. For that reason, it strikes me as quite contemporary; a hammier version of the overly personal tone we still seem to require of our criticism and our critics. It’s a bid at intimacy that offers a false peak behind the curtain of a review. Or, while we’re in the realm of theatrical metaphors: a fourth wall break.

But it’s also wry and petty. The informality that makes it more authentic also makes it meaner, more callous. Nathan is having too much fun exaggerating this persona for dramatic effect. It’s pompous in its drama. ‘[T]he best dramatic criticism’, Nathan writes in the aptly named The Critic and the Drama ‘is always just a little dramatic’. Humour me for a second as I imagine the theatre critic as a ‘diva’, or an ‘actor’. Critic Declan Fry drew a similar comparison in Kill Your Darlings as recently as 2021, singling out the shared ‘late nights, the furious desire to please your audience’. Again, we’re back to understanding this bid at intimacy as a way to connect to his readers (his audience). Those who’ve seen Back to Methuselah might chuckle at the relatability of his review, or roll their eyes at its attempt to hyperbolise experiences they shared (at least a little bit). Those who haven’t seen it can enjoy imagining its experience with some chagrin or schadenfreude.

Bernard Shaw knew Nathan pretty well when this review came out. ‘[I]intelligent playgoer number one’, he called him - the kind of observation that I guess could be bitchy if you said it in the right tone. It’s New York in the 1920s - who isn’t a bitch? The material impact of any review is hard to quantify. But Back to Methuselah didn’t last long on Broadway. It closed earlier than expected at a loss of $20,000.

I wonder what you think of the subjectivity I’ve presented in this newsletter thus far, or in any of my reviews. I’ve managed some occasional quips; I’ve leant into the personal air of Substack as a medium (a more easily marketized echo of the confessional blogs of the 00s). But I can share more! I have back pain and gas I promise! This newsletter is a labour of love, but it’s also a labour I feel under my eyes. Would you like to know about my rent? Or my upbringing? I’m a child of divorce, if you even care.

But that’s not the ‘critic’ I’ve constructed here. Melbourne International Comedy Festival is over. The chances that one of the many reviews I wrote during that festival might have forced a show to close down is unlikely - no matter how acerbic my opening anecdotes, cruel my take downs or critically rigorous my dialectic might have been. But it is likely that one my reviews has hurt someone, and will again. It’s with that admission that I return to the prospect of reviewing my friends. At the core of this newsletter is a deeply personal sense of stakes. Because I don’t want to lose these friends. The problematic undergirding these reviews is whether the intimacy of such an admission can marry with the authority of a critical persona, or the formal and material conditions of criticism. Am I reviewing them as a friend or a critic? Can you tell, either way?

I think about Lou Wall, Mel O’Brien, Samantha Andrew, or Jarryd Prain reading their relationship with me in a review, a star rating, or a pull-quote. I think about what observations might hurt each of them. Can I ever write a review without imagining them as my sole reader? Where does a ten year friendship go in a review form - or the form a review takes in a Substack newsletter, a 100-word piece for Time Out, a conversation at stage door? Should it go further when it’s priced at $60 for 800 words? Or $150 for The Age? I think about anyone else reading a review with these contexts in mind suddenly sensitive to detecting bias in my style of writing, or the content of my critique. What would they notice? This insular city at the feet of my star-rated subjectivity. My critical authority! Dashed! What would it take for a reader to accept my form of bias as complimentary, rather than detrimental to my criticism? What would it take for a review to destroy one of these friendships?

Andrea Long Chu opts for a gorier metaphor than Nathan when she describes the inevitably personal nature of criticism that feels important here: ‘No critic manages to cut out her heart and hide it under the floorboards without leaving a little trail of blood’. I like it, mostly because the absent personal pronoun at the end opens it up to a possibility that it’s not necessarily the critic’s heart leaving a trail behind.

Lou: five stars, one bag of Red Rock Deli Chips

So I start my ‘review’ of Lou Wall’s Breaking the Fifth Wall at this year’s Melbourne International Comedy Festival with something personal - like the fact that I’m thinking about the time I brought them a bag of Red Rock Deli chips when they were sleeping on my couch in 2023 as they walk past me. Call it a peak behind the fourth wall of a Substack newsletter. Or just personal context (did I mention my lower back pain?).

I’m also thinking about the relationship between form and content in comedy as I’m watching , or the specific relationship between them Wall is interested in exploring. Early on, they propose a ‘fifth wall’ exists between comedians and their audiences. The idea is that we’ve already implicitly stepped over the fourth wall when we walked into the Comedy Republic to see them. Belief is suspended from the start, in other words: we come in with the presumption that what we’re about to be told is true. Who doesn’t want to trust the reality of every stand-up’s off-the-cuff observations and personal anecdotes? If authenticity is the beating heart of stand-up comedy, then lying authentically is the bread and butter of any successful comedian. Forget telling your audience what is true and instead learn the form lying ‘truthfully’ takes in 2025. Wall argues that authenticity is a question of style, rather than content for an hour.

It’s not a new idea - all art entails the play between artifice and reality. What is new is the form it takes in Wall’s show. From Lou Wall vs The Internet in 2021 to Bisexual’s Lament in 2023, Wall’s style of comedy has been formed explicitly to reflect the particularities of the internet: its self-referential humour, its self-ironising tone, its pursuit of authenticity, its suspicion of authenticity. Wall runs us through the many lies they’ve told as a comedian, wielding a clicker in their hand like a gun that fires off one slide after another packed to the brim with memes, doctored photos, falsified videos and metatheatrical games Wall plays with the near-dead pan irony typical of the Gen Z comic.

Who knows better than the most chronically online generation how creative we’ve become at blurring the line between what is real and what isn’t; and how often we evaluate that line according to levels of authenticity we pretend we no longer crave. Jia Tollentino opens her essay ‘My Brain Finally Broke’ for The New Yorker talking about the way we’ve internalised this ‘blurring’ of the line between reality and artifice as a blurriness in our heads: ‘a troubling kind of opacity in my brain lately - as if reality were becoming illegible’. Unable to recognise what is real, we are sensitive to authenticity - not as evidence of some absolute reality, but as a feeling that there might still be an absolute reality we can recognise.

No wonder comedies like Nathan Fielder’s The Rehearsal, or John Wilson’s How to With John Wilson have resonated with so many. Like Wall’s show, they achieve more authenticity by recreating that seasawing un/reality of our online world in a way that evokes something truer to our everyday experience.

But Wall is in conversation with the specific form of authenticity that dogs at the heels of AFAB comedians whenever their shows lean toward the confessional - or even explicitly away from the confessional - form. There’s a moment near the end of the show when Wall talks about the time they had one of their first stand-up gigs reviewed as a fresh-faced nineteen-year-old. They’d written something confessional, or what they thought a confessional show was: a tight ten assembled from personal anecdotes and observations pulled right out of their real life. It’s an approach that came out of a time (2014) when there was still something novel about the personal essay, politically radical about memoirs, and self-empowering about self-important art. An economic pathway to success loomed: personal stories appear authentic, authenticity fosters a closer connection to an audience and gives you more laughs; more laughs gives you a Netflix special (or a Golden Gibbo nom at least). When Wall received a review of that set soon after, every criticism was suddenly painfully intimate. They had broken the fifth wall and bared their soul for a critic to weigh.

One morning when they were living with me they asked if I’d have a coffee with them. They wanted to get my honest review about the show they were doing at the time, Lou Wall vs. the Internet. I was honest with them. But I wouldn’t have written a review of their show: I wanted to be friends with them. I didn’t this year, either. Even though we’re no longer friends.

Kidding, imagine. But when would I feel comfortable enough to review them?

One of my favourite Naarm-based reviewers, Dianne Stubbings was asked how she feels ‘about reviewing people you know’ She replied, simply: ‘I have a strict rule against it.’

Define ‘know’.

When I was starting out I reviewed a mate’s show at Theatre Works, unpaid, for a blog. I gave it four stars and took a date with me. I stand by those four stars even now, but I would: my mate is still my mate. My date questioned my bias afterwards. They were right to. I wouldn’t review that show now, not because I was kinder to the show. In fact, the opposite. ‘Often, critics are negative because someone we like - perhaps even love - proved disappointing,’ Declan Fry wrote in the beautifully-titled ‘Negative Reviews, Positive Vibes and Being a Forever Reader’ in 2021. That date did a show at Theatre Works last year, which I didn’t review. But I wouldn’t: he’s no longer my date. I don’t love him enough to be okay with hurting him. If only I’d hidden a second date option in a five star review for him to decode.

My point is that there is an ex-situationship in independent theatre everywhere for those with eyes to see. My point is that there is bias everywhere for any critic in this city. We all know that, but we don’t do much with it. Nor can we. What is the objectivity we were once looking for from criticism? What does subjectivity need to look like in our criticism?

When we say no one can be fully objective, what we’re often talking about is positionality. ‘I don’t know what I don’t know’ is the limit that discussions of positionality—I’m white, I’m University-educated, I’m gay, I’m a Leo—expose, and that subjective criticism uses to its advantage. Ben Brantley wrote in his exit interview for the New York Times of being inevitably ‘trapped in the shells of our race, class, gender and generation’. Brantley overstates the limiting quality of these shells we’re ‘trapped’ in with the air of a very well-meaning Boomer liberal doing 2020-politics. I think good critics understand positionality in 2025 as a means into more knowledge, not less (while simultaneously acknowledging that we live on a continent that continues to dispute the very notion that positionality means anything at all). In good criticism, it’s a prompt to ‘connect’ better to subjectivity—which I think of as a dynamic ‘relating’ between one’s personal subjectivity and the intermingling, mutable form(s) of subjectivity we see play out on (and around) our stages. It’s critic Kyle Turner who floats this idea of ‘connection’ interviewing Andrea Long Chu - writing ‘with our social and material realities’ as one part of writing subjectively that includes ‘marry[ing] aestheticism, judgment, and, most of all, living in the world.’ Our selves are never static in the world, so why should our criticism be?

Mel: five stars, one Carlton sharehouse, one Fitzroy sharehouse

I walked back from my coffee with Lou to bring some Chicken Shapes (an era of gifting chips apparently) to my housemate: Mel O’Brien. I think about that moment when I’m watching Mel and her comedy partner, Samantha Andrew in their show for this year’s Melbourne International Comedy Festival, No Hat, No Play! But I also think about the dynamic between form and content that has characterised their work since the pair first performed this show back in 2020. I’m also laughing, promise.

Less than thirty seconds in and I recognise the Mel & Sam-isms that have become their signature: reverential musical comedy numbers, queer chaos in a cabaret frame. They’re two Gen Z (cusp) theatre kids ‘yes, and’-ing each other from one referential sketch to another propelled by the strength of their combined charisma and authenticity. No Hat, No Play! was their first show as a duo. It is something like a Rosetta Stone - all the work they’ve put into developing a brand and a recognisable style over five years preserved in every line, beat, and harmony like amber gris. They were doing a different show when Lou was on our couch in 2023: High Pony. I think about Mel showing me the copy she’d written for the show’s synopsis while we sat on her bed together. I remember reading it and having notes. She must’ve seen those notes in a glint behind my eyes. I remember her quickly stopping me. “We’ve already sent it off!”

A week after they close, I sit with Mel in a park in the sun. She talks about the season and the pressure femme-presenting comedians have to make confessional work rather than work that is just unashamedly silly to be taken seriously by critics. Trauma-based content vs. formalised tomfoolery. It’s something that frames Lou’s show too, which came after The Bisexual’s Lament: a more confessional show recounting a break up they went through.

We know ‘confessional’ means something different for a male comedian than it does for a female, or femme-presenting comedian. The difference informs everything: how the confessional style is internalised, what form it takes, what form audiences accept it taking. Nathan Fielder and Tom Wilson’s post-modernist approaches to confessional comedy are more commonly evaluated according to the questions they ask of the form than the personal narratives that they use to hang those questions on. When Season 2 of The Rehearsal (*no spoilers) ends by teasing us with a personal revelation one that would paint the entire show as a more explicitly confessional piece—the intimacy of the moment feels novel. I don’t think it’s wrong to say that this moment would be more likely to be analysed as an example of Fielder's control of the formal qualities of comedy itself—or a political commentary—rather than as a personal metaphor for some humanist reading on our collective experience as people. The latter reading is so often reserved for female writers. Yes, Fielder wears his formalist intentions on his sleeve; and yes, his work has been understood as personal. But his ability to perform such a personal narrative without it outweighing that metacommentary is informed by a long-held gendered assumption that requires confessional forms from AFAB people and treats the same forms from AMAB people as novel.

Mel and I are still sipping coffees on the grass when she shows me a two-and-a-half star review for No Hat, No Play! from legendary British reviewer and critical hatchet-swinger, Chortle. I have a soft spot for pans but the review is boring for its patronising dedication to diminishing the work Mel & Sam dedicated to the show’s style and form. ‘[T]he loosest of plots’, he writes, ‘ideas are half-baked’; ‘maybe Mel and Sam just got lazy’. Mel tears up a bit. Back when we were living together we used to chat about bad reviews, or review bad shows constantly. I ask her if she wants to read my review of No Hat, No Play! before I publish it here. She says yes, though I warn her ‘it won’t be without notes’ (a line that Mel suggested actually - love you xx).

Jarryd: five stars, twelve years of friendship.

When I’m watching Jarryd Prain in his first comedy show, The Hanky Code, I think about our twelve-year long friendship while I laugh through an hour of punchlines about piss kinks and the Pope (RIP); 9/11, Lea Michele, and sexual shame. It’s the first time I’ve seen him do stand up in person, but it won’t be the last time he’ll make me laugh (unless I destroy our friendship with this newsletter). I see the show twice because we’re friends and because I asked him if I could review it (or try to). Near the end of the show he talks about his experience of being groomed during an amateur production of Peter Pan when he was a teenager. I know who he’s talking about. We met in the next production that the director put on.

I sit down to write my review of Jarryd objectively first. My star-rating knows nothing of our friendship. I let it fall away for the cooly detached authority of its sharp points. One Star for his rapport with the audience. One more for tight writing and his nuanced observations about contemporary gay sex (<3). Take away half-a-star for the time he went to a bathhouse without me, and another for not laughing at my joke in the group chat just now. Add one more for his adlibs, and take away one for the pacing issues that make the show’s confessional moments a bit jarring tonally. I take that back actually: he laughed-reacted to my joke. Or maybe I should take it back because I know the truth behind those confessional moments first hand. I know that it was in the process of thinking through questions of form and style for The Hanky Code that led Jarryd to name that moment the way he does—as if it was from behind that comedic ‘fifth wall’ that he could encounter a truth and safely feel its authenticity.

Lou sends me an instagram message in early 2024:

‘Guy guy guy. What do you think of the concept of comedy = tragedy + time?’ ‘Something about contemp comedy strikes me as super interested in how much time / what kind of tragedy (trauma plot, etc) qualifies…nothing more exciting and dangerous about seeing one think through personal tragedy through comedy - and also with Gen z / queer comedians using and loving irony so beautifully I think it’s all a matter of self awareness and a really discerning use of earnestness

Srry talking in broad strokes obviously but like I think of the nannette turn lmao or the millennial tendency to feel that the tragedy / comedy line needs to lead to an earnest thesis or emotional payoff and I say nah boring - finding a way to be truly vulnerable / toy with how alive and dangerous it can be to see someone share personal tragedy and find comedy in it comes from not insisting on its importance / not over curating an audiences emotional reaction.

When I was watching their show, The Bisexual’s Lament at last year’s Comedy Festival, some of Lou’s anecdotes seemed familiar. Much of the show’s one-hour runtime was dedicated to telling the story of a break up, one they went through while on Mel and I’s couch back in 2023. Tragedy over time.

While I’m editing my reviews for this newsletter, Jarryd finishes a season of The Hanky Code at the Enmore theatre in Sydney. I know he’s moved back home with his parents to save money. I know that he’s working everyday in the city and crashing with a friend nearby. He messages ‘The Pumps’ (our seven-year old group chat) the day before his opening night having just received the bill for the queer venue on Smith Street he performed in during his Melbourne season. It’ll be $2000+. He’ll lose money. I think about the ethics of pitching to interview him for some of the smaller publications in Melbourne to help with his ticket sales. But I post on my Instagram story instead. I think of Mel mentioning how disappointing ticket sales for No Hat, No Play! were during her season. She messages me while I’m editing this paragraph: ‘just thinking about you, love you’. I don’t know what Lou is doing. I don’t pitch to review them this year, though we haven’t spoken in years. They get a five-star review in The Guardian and perform a part of their show for the Comedy Gala that goes viral.

I think about how many stars I’d give them as they walk back onto the Comedy Republic stage to finish their show. Then I keep laughing. It's comedy, after all. And they’re a mate.

To be continued with Part 2: My Bias and Mel & Sam’s No Hat, No Play!

Interesting read!